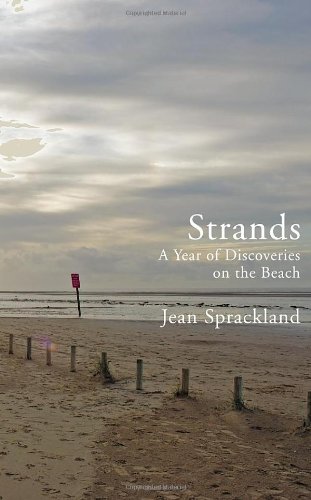

Strands

WINNER OF THE PORTICO PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION 2012

A series of meditations prompted by walking on the wild estuarial beaches of Ainsdale Sands between Blackpool and Liverpool, Strands: A Year of Discoveries on the Beach is a book about what is lost and buried then discovered, about all the things you find on a beach, dead or alive, about flotsam and jetsam, about mutability and transformation — about sea-change.

Every so often the sands shift enough to reveal great mysteries: the Star of Hope, wrecked on Mad Wharf in 1883 and usually just visible as a few wooden stumps, is suddenly raised one day, up from the depths — an entire wreck, black and barnacled, and on either side two more ruined ships, taking the air for a while before sinking back under the sand.

And stranger still, perhaps, are the prehistoric footprints of humans, animals and birds on the beach: prints from the Late Mesolithic to mid-Neolithic period which are described as ‘ephemeral archaeology’ because they are preserved in the Holocene sediment, revealed briefly and then destroyed by the next tide.

This is the ultimate beachcomber’s book, about a year walking on the ultimate beach: inter-tidal and constantly turning up revelations: mermaid’s purses, lugworms, sea potatoes, messages in bottles, buried cars, beached whales, a perfect cup from a Cunard liner. And Jean Sprackland, a prize-winning poet and natural story-teller, is the perfect guide to these shifting sands — this place of transformation.

“Elegant memoir. For those for whom such encounters are a rare occurrence, reading this beautiful book is only a tide’s whisper away from being on a beach itself and feeling the wind in your hair and the sand between your toes.”

“Compelling...well-contextualised, sharply-observed, clued up, environmentally aware and deeply researched. She writes a supple, attractive, gently ironic prose that brings alive this distinctive shoreline.”

Excerpt

I haul my bike over the high sandbar and cycle to the first wreck, far out near the sea’s edge. It’s a wooden vessel, very well exposed, with a sturdy post which might have been a mast, and curved wooden spurs like the ribcage of some extinct beast, picked clean of its flesh by the sea.

I cycle on to the second, an old favourite. It’s the Star of Hope, a wreck I’ve visited several times on occasions when the sand has yielded it. It’s lying forlornly in muddy water, heavily barnacled, black and rotting in places.

The third, further north and closer to shore, is huge and listing, spilling its cargo of wet sand. It’s a more solid sort of craft, and I’ve never seen it before. The deck is missing, but there is a framework of bent spars with iron knees which must once have held it together and now give some idea of its size. There’s a contraption which looks like a windlass for winching freight on board or for raising the anchor.

When I say that this place is changeable, this is one of the things I mean. The tides and currents conspire to move and reshape the sand, and in the intertidal zone a skeletal old ship emerges. The rest of the time it’s buried and invisible; people and dogs walk and run over it with no idea that it’s there. Then, without warning, it rises to the surface. It takes the air for a few weeks, before subsiding into the sand again.

I first experienced this on a spring day five years ago, when a friend called in a state of high excitement and read out an article from the local paper, under the marvellous headline Boat sunk in storm rises again. According to the report, it was the first time in seven years that the Star of Hope had come so completely to the surface. Once wrecked, she was claimed by the sands, which stowed her away underground, working her to the surface only occasionally. No one knew how long she would remain visible, so my friend and I arranged to meet on the beach, along with our teenage sons, and catch a glimpse of this phenomenon while it lasted.